We have all been there before

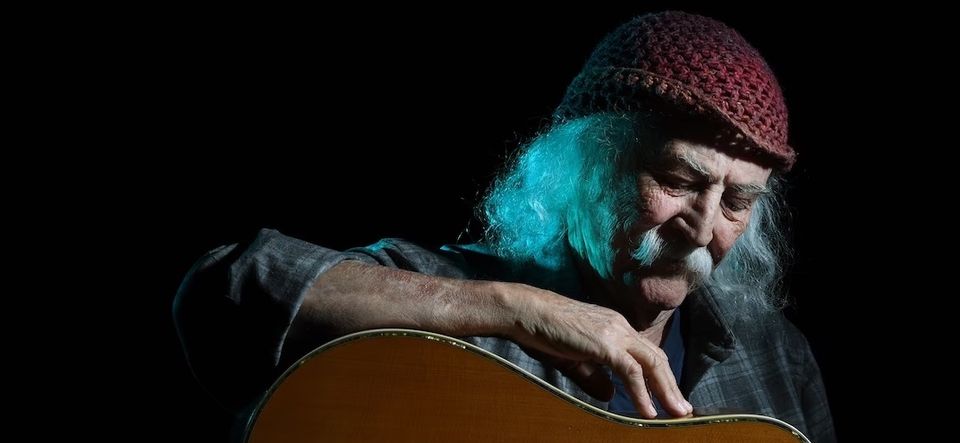

Or, the passing of David Crosby, unanticipated exemplar

The elementary particles of my creative work are memories. I ask people what they remember seeing, hearing, thinking. I read what writers recall seeing, hearing, thinking. I sit before a blank page and ask myself what I remember seeing, hearing, thinking. My photographs too are built on memory. Remember how that felt? That’s what I tried to capture, that’s what I need to convey through this image. So I think about memory a lot. Much of my work comes down to me laboring to remember my memories.

Every day, every hour we summon memory and sip from it. This doesn’t register as phenomenal — we need to recall something and just do it. In a subconscious way we tap our mind for the last time we saw a friend, the name of the guy walking toward us, how long the chicken needs to be in the oven, a joke, an insult, a compliment, a face, a lyric, or where we last saw our sunglasses and dear lord let it not be on the roof of the car, again.

Sip-thought occurs in language, we hear it speak in our minds. But there are memories that flash-flood our being, and they don’t come through words. When we ponder, when we quiz ourselves, when we rack our brains trying to remember, we don’t suddenly find ourselves bathed in savory sensory experience. Bathed in frustration, maybe, but not Proust nibbling a madeleine. We may speak of a favorite literary passage as “transporting,” but it’s not, not really, because words mediate experience while sense memory unmitigated by language recreates experience, sometimes with a vividness that startles us.

A whiff of the after-shave lotion favored by my father sends me back 65 years, snugged against him on a worn sofa as he reads the Sunday paper; he’s big and strong and wearing paint-spattered khakis and a white t-shirt and he’s silent and absorbed but still keeping me safe from everything. On another day, a few measures of Cat Stevens singing “Wild World” brush my ears and next thing I know I’m 16, riding in a dreadnought of a pink car driven by an older girl whom I have a crush on and it’s the end of spring and the school year is over and she’s about to move on with her life, which will not include me. I know this with a bittersweet realization that leaves me less sad than pensive; something in that adolescent boy stirs with the inarticulated understanding that he's just experienced grownup wistfulness for the first time. I want to kiss her but I don’t.

For an incandescent moment, I am there.

I’ve been thinking about all this since I learned that David Crosby died last week. My formative years were the 1960s and ’70s when nothing mattered more to me than music. Books were there, too, always books, but reading was like a drone note under the urgent, propulsive songs that channeled my life. I could walk away from Vonnegut and Fitzgerald and Kerouac and Hesse and Pirsig for a while, but never the Allman Brothers Band or Santana or Springsteen or Crosby, Stills & Nash.

Decades on in my life, certain songs propel me back to long past moments at the speed of light. The moments don’t have to be dramatic; most of the time they’re not. But they’re still vivid. I hear the G5/D arpeggio from Crosby’s 12-string guitar that opens “Deja Vu” and I’m in the back of an arena for a Crosby & Nash concert, November 1973, seated next to my girlfriend as the stage lights come up for the first time and the fuzzy, rotund Crosby has begun finger-picking that chord on a red electric guitar and I think, Oh, here we go, great song. (Or, I’m in a car again, this time with a neighbor kid and we’re on our way home from working the night shift at Arby’s and “Deja Vu” comes on the radio and he turns it up, which surprises me because he’s kind of a lunk and I didn’t expect him to like this one. The same song can move me around in time; I don’t always land in the same place.)

Pop music moves in on our hearts about the time hormones take fun, charming kids and turns them into volatile, pissy teenagers. Well before we figure out what it means to love a girl or a boy, we fall in love with a band that saturates our life with color and sound and raw energy, all turned up as far as the dial will travel. Back then, your favorite song could blot out everything for four minutes and make you so happy you nearly burst.

Your life might not have been great, it might have been rough and sad, but your years of loving the bands probably were among your happiest. That’s why we crave the way music can reel us back. But while happiness can seem like the promised land, it’s not. We need to live a good bit of life to understand that happiness, for all its diverting charm, is shallow, and holding on to it can be like trying to hold smoke in a spoon. We learn, if we’ve been paying attention, that it’s possible for life to be much more than happy — it can be rich. Rich includes happiness, but it’s seasoned by poignance, sadness, fear, joy, pain, and loss, all the smart stuff and all the dumb stuff, what we remember and what we suspect or fear we’ve forgotten, moments we wish we could reinhabit and moments we hope never to experience again. Happiness is quicksilver, slippery and elusive, and for all its seductiveness not that much use. Leave it in a drawer with that faded Clash t-shirt and pursue richness. That said, now and then take a moment and turn up “Won’t Get Fooled Again” and thrash at an air guitar. It will do you good. (Past a certain age, it’s best if you do this alone.)

David Crosby apart from CSN didn’t figure that much in my youth. But his passing saddened me because I’d come to respect what he’d done late in his life and I wanted him to have more of it. As a young man, he was an asshole. He alienated just about everybody, lost just about everything, ruined his health, spent months in jail, wasted decades that he could have lived making art. Then, in his 60s and 70s, he stared himself down, squared up to what he had become, got clean and as healthy as he was going to get, and forged the most artistically productive years of his life. There’s no exaggerating how hard that must have been.

I’ve taken a lot of things from his life and music. Some of the parallels make me wince. As a young man, he was an asshole? Well, so was I. (He was worse, but he had a lot more drugs and asshole friends.) Maybe I’m being harsh, maybe I was just a jerk, but it took me an ungodly number of years to grow up and understand that you can’t make a life that matters — and art that matters — by wrapping yourself in some thin cheap identity that you anxiously force on everyone. Your first day as an artist, and your first day as an adult worth being around, is the day you realize that you have to shut up and listen — listen and listen and listen until that other punk has slunk away and you can start to hear your own true story, the one that was always there while you were busy being 14. It’s a lot of work and at times it will hurt, but not until you enter this stillness and silence and openness to your life’s truth will your skin finally fit. Only then can you start to tell, and through that telling understand, the tale of your one wild and precious life. And create something worthy of another person’s attention.

If you are as lucky as I have been, you will find that 40, 50, 60 years on there are people who for some reason didn’t just tolerate you, they never stopped loving you. They are still around and now you get to love them back. That’s a song you can dance to for the rest of your days.

Thanks, Croz. Thanks for all the music, and thanks for the example.

Member discussion