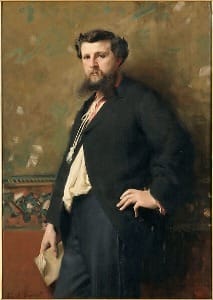

John Singer Sargent’s hands

This gentleman, who may be wearing a bathrobe and does not look displeased with himself, is Dr. Samuel Jean Pozzi. He lived in France from 1846 to 1918. The esteemed biographer Leon Edel described Pozzi as “a society doctor, a book-collector, and a generally cultivated conversationalist.” Alice, Princesse de Monaco, described him as “disgustingly handsome.” His extramarital excursions included stops at the bed of Sarah Bernhardt.

The good society doctor is the central figure in Julian Barnes’s fine 2020 book about Belle Époque Paris, The Man in the Red Coat. That he does not look displeased in the portrait might be, in part, because of his portraitist—John Singer Sargent. Who would not be happy about sitting, or standing, for that gentleman’s painterly attention?

I viewed the picture last July at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, as part of its superb “Sargent & Paris” exhibit. My painter father taught me to systematically and meticulously examine all aspects of a painting. Following his instructions with Dr. Pozzi at Home, I felt my gaze settle on the subject’s left hand.

Pozzi’s hands, as rendered by Sargent, have attracted attention before. “Society doctor” was a bit of a euphemism; Pozzi was a gynecologist, one with, presumably, clients who enjoyed the same social status as Sargent’s other subjects. (He is considered a pioneer in gynecological practice.) The coincidence of his medical specialty and Sargent’s handiwork has inspired commentary like this, for example, from Leslie Cozzi of the Grunwald Center for the Graphic Arts:

It has been suggested that the emphasis on the hands may be a reminder of Pozzi’s trademark examination method that involved manual exploration of his female patients’ anatomies. More recently, the art historian Alison Syme has read the delicacy of Sargent’s painted hands as ciphers of homoerotic desire.

Well, okay. That coy “it has been suggested” might suggest some reluctance on the part of Ms. Cozzi to join in that opinion. James Payne, creator of the video series Great Art Explained, is more forthright. He calls the picture “a boudoir portrait,” its subject “oozing sex appeal.” Payne observes:

His left hand sits limply on his hip and he fingers a red cord, with a dangling tassle hanging heavily between his legs.

That’ll be enough of that. Think of the children.

I confess, my own mind went neither to sex nor gynecology, but to contrast. First, look at Pozzi’s right hand, up near his throat. Sargent rendered it as graceful, dexterous, precise. In contrast, the left hand has a claw-like angularity and tautness. I didn’t think much of it at the time, but made a mental note.

Then I came to Mrs. Albert Vickers (Edith Foster), painted in 1884.

Her right hand, which pulls your gaze from her face, holds a white flower. Her left?

A gleaming ring, two fingers curling inward, and the pinkie at an angle that, to my eye, looks tensed.

Next, the elegant Madame Ramón Subercaseaux (Amalia Errázuriz y Urmeneta), seated at a piano.

The Met’s description said she appeared to have just paused in her playing, but not if you look at the angle of the chair. Anyway, yes, the hands...

I found that when I casually draped my own hand similarly, I had to flex to get the near right angle of the forefinger and wrist. Another portrait of a seemingly relaxed subject exhibiting a tensed hand and wrist.

This gent, with the funny beard, was the poet and playwright Edouard Pailleron. Another Sargent portrait in the show of someone holding something—robe, flower, chair, manuscript (perhaps)—in one hand. Now, look at the other...

Not an unnatural position, by any means, but that little finger looks pulled back. Snagged on fabric? Not likely, I think, given where it rests on the poet’s jacket. But if it’s not snagged, then what? Looks drawn back to me.

I have no idea what Sargent was thinking when he painted these hands, no idea if he intended some meaning or had just daubed some paint on the canvas, looked at the crook of a finger, and thought, Huh, I sort of like that. Declaring what an artist intended without consulting the artist is usually the road to silliness. And I don’t really care what John Singer Sargent may or may not have been saying through Dr. Pozzi’s right hand. I just like that in these commissioned portraits meant to flatter sleek, prosperous, high-status people, Singer has included bits of tension, hints that even these privileged lives were not without friction, and no matter how self-satisfied the subjects, perhaps they were not entirely at ease before the artist.

Coda

- If you would like to see thumbnails of all the pictures from the Met’s show, go here.

- Sargent painted his notorious Madame X, Amélie Gautreau, more than once. There’s the famous, scandalous picture, the one with the black dress and the wandering shoulder strap, and a more sedate picture, Madame Gautreau Drinking a Toast. The latter sold around 1884. The buyer was Samuel Pozzi.

Dr Essai cannot depend on high society for his stipends. If you believe this is a social injustice, you can become a voluntary paid subscriber. Far less ostentatious, yet a rewarding experience, all the same.

Member discussion