Onward to the Path of Totality, followed by a moonshadow

Letter No. 79: Includes much casual use of the word “saros,” some old astronomy, and not much ineffable.

A saros is an esoteric unit of measurement that was known to Chaldean astronomers. Those guys predated the Babylonians, more than five centuries BCE, so it’s an old measure, too. A saros is 18 years, 11 days, and 8 hours. It is also 223 synodic months, 241.999 draconic months, 238.992 anomalistic months, or 241.029 sidereal months.

I always thought a month was a month. But when you’re talking about the moon there are four different types of month, and I am talking about the moon because a saros is the time elapsed between solar eclipses. Paging ahead in your calendar by one saros to mark the next occultation is so much easier than paging forward 6,585.321347 solar days, which is another way to count the interval. So many decimal places.

But wait, you say: every 18.03 years? Was there not a total eclipse over the United States in 2017? Yes there was, so let me sharpen the focus: a saros is the interval between eclipses of nearly identical astronomical geometry, what is called syzygy. So the 2017 eclipse was, mathematically, not exactly like the one that I just observed on April 8, 2024. Astronomers group eclipses into saros cycles, eclipse families, and the 2017 show was part of Saros 145. This year’s was part of Saros 139. Eclipse chasers are fond of Saros 136, because through the 21st century it will produce the longest periods of totality.

One-half of a saros is a sar. I think that’s about enough on that topic.

My wife and I ventured from Baltimore to Connersville, Indiana to put ourselves in Saros 139’s Path of Totality, a phrase that meant nothing to me a month ago. The 2024 PoT was a trail of moonshadow that stretched from Texas to Maine. Tom and Carol, Cincinnati friends I’ve known for more than 50 years, had scouted locations and decided Connersville was optimal. Rural roads took us through towns, past farms, past a giant “God, Guns and Trump” flag. This part of Indiana is flat as a griddle. Tom kept his eye on the road and we kept our eyes on the sky; the forecast had predicted 20 to 40 percent cloud cover, but Tom pointed out that he and Carol were the couple who’d spent a dozen or so days in Ireland and been rained on only once.

About three hours before the moon started to scallop the sun, we pulled into a park. A young woman wearing a black “Connersville Solar Eclipse 2024” t-shirt collected 10 dollars and directed us to a space next to a farmer’s field. We set up a table and chairs and set out food and got to know a few temporary neighbors who were old enough to appreciate Carol’s special “Hello Darkness My Old Friend” eclipse shirt. The sky had begun veering toward clear which put us in an ever-better mood as we settled into what the writer Willa Glickman recently called “an exercise in collective expectation.”

After I set up my camera, I had a few hours to think about all of this. Most days my mind oscillates between the literary and the nerdy, and as I leaned against the trunk of Tom’s car I thought less about the cosmic meaning of it all than about the improbable math. That we might see the sun’s corona required such an unlikely convergence of spherical dimensions, disc diameters, Newtonian orbital mechanics, and angles of vision. The moon is 1/400th the size of the sun but the sun is 400 times farther away, so every 18.03 years of Saros 139 they line up just so. There’s a woozy but interesting practice known as sacred geometry, and this coincidence of heavenly bodies is enough to make you see how some people might be drawn to it.

About 1:30 pm we shielded our eyes with dark film and looked up. The sun was missing a bit. Showtime.

A total eclipse takes a while. The mean orbital velocity of the moon is almost 2,300 miles per hour, but it has a lot of ground to cover, so about 90 minutes elapse from first black crescent to totality, and for most of that time there’s little to see. It’s what you might call a slow build. Logic says that when 75 percent of the sun’s disc is obscured, the ambient light should be dimmed by 75 percent, but no. The temperature drops and the wind picks up before the light dims. This is partly because our eyes are slow to adjust to changes in light, and partly because…I don’t know, I couldn’t find more of an answer.

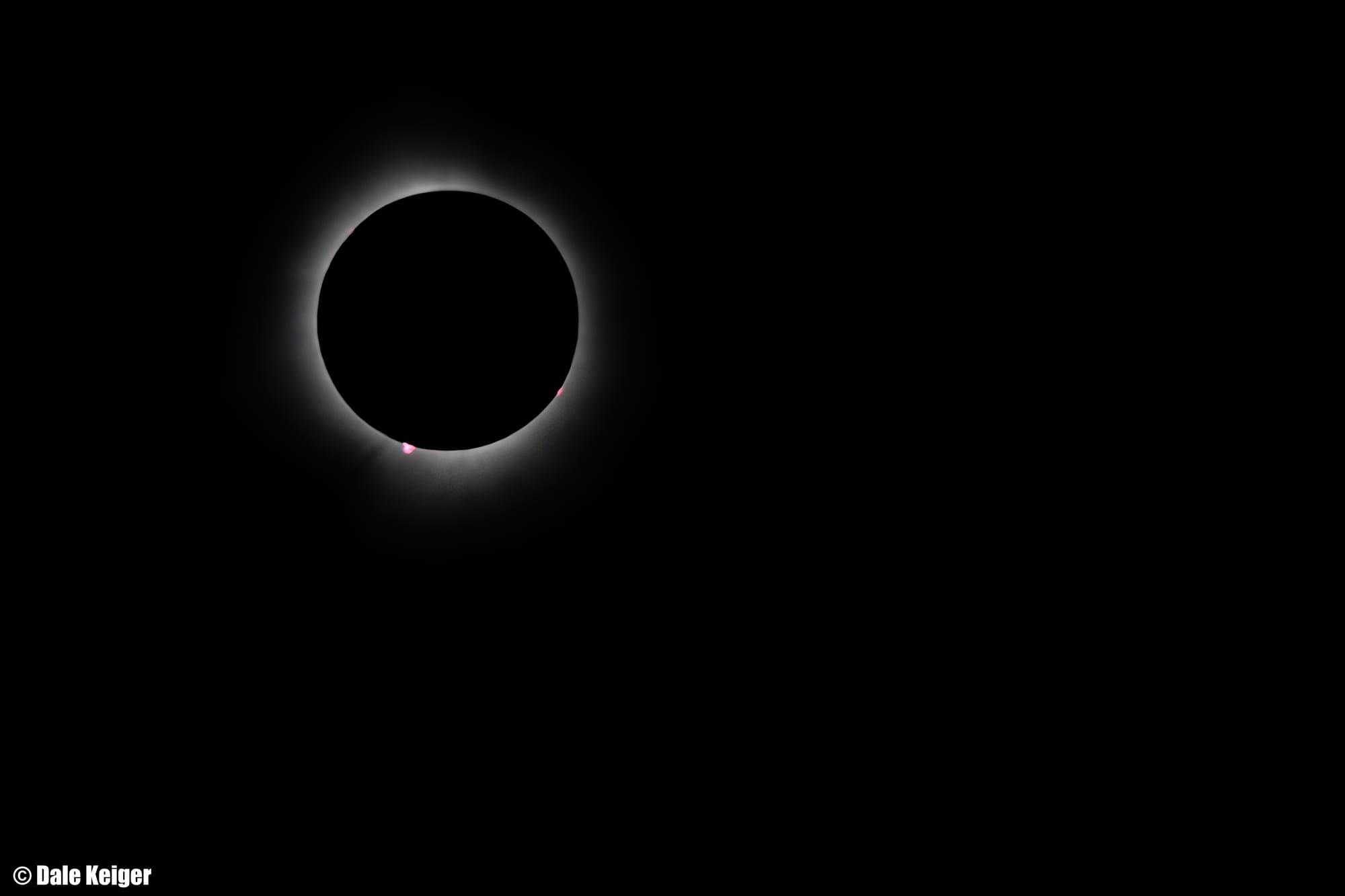

The last seconds were dramatic. We had a clear sky—Tom and Carol’s Irish luck held—and my wife cried out at the flash of Bailey’s beads: the last photons of direct sunlight blazing through valleys along the moon’s circumference. The first record of the beads is circa 1715 by Sir Edmund Halley, but they’re not named after him; he had to settle for that comet. The namesake, Francis Bailey, got the honor because he correctly explained the phenomenon in 1836. His paper in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society includes this lovely description:

...when the cusps of the sun were about 40 degrees asunder, a row of lucid points, like a string of beads, irregular in size and distance from each other, suddenly formed around that part of the circumference of the moon that was about to enter on the sun's disc.

Can’t improve on that. Well said, Mr. Bailey.

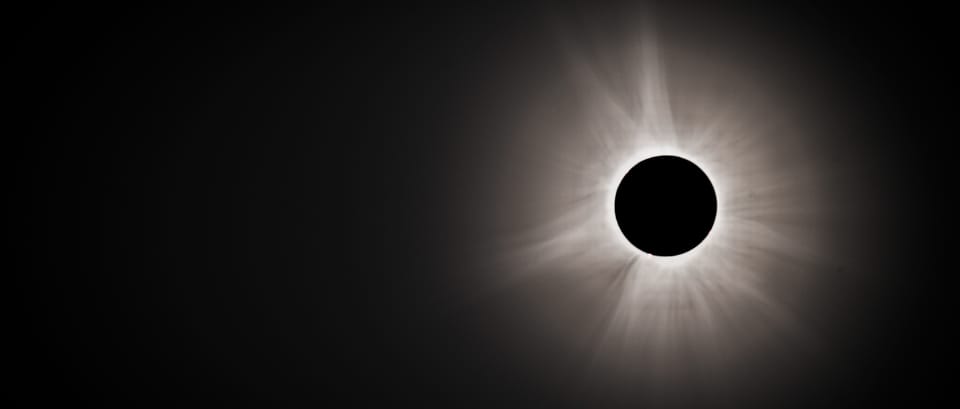

Then, of a sudden, 3:40 of total eclipse. Automatic lights in the park and on the neighboring farm winked on as the sun winked off. I don’t recall hearing anything as I gazed at a black hole in the sky surrounded by flaring luminescence. Probably a few of us cheered or exclaimed, but I don’t remember. I was that focused on my eyes. I squeezed a remote shutter release to grab a series of images with my camera and then tried to stay in this moment. I am 70 years old, which means it is ever rarer for me to think, I have never seen anything like this before. And I understood one more thing: this was the one time in my life I would have this before my eyes.

Three minutes and forty seconds of such an experience go by in no time. With a fast flash, the diamond ring effect came and went and the sun began to reappear. Turns out it had been back there all along, which for millennia must have been a relief to pre-science humans.

It’s really hard to describe a total eclipse without resort to cliché. It seems even harder to resist reaching for meaning and the ineffable, and in the attempt falling on one’s face. Total eclipses inspire an awful lot of gibberish. Pamela Paul, the New York Times columnist, is a smart woman, but that didn’t prevent the first line of her April 8 column: “Maybe it takes an extraterrestrial event to bring this shredded country together.”

Yeah. That night back in our hotel, my wife and I tuned into the local Fox News affiliate to hear about the eclipse. Ten minutes in, the newscasters still hadn’t gotten to it because first they had to cover three incidents of violent crime committed by African Americans. The fourth story was about a violent crime committed by a pair of Latinos. So much for deshredding the country.

In the build-up to the big event, I encountered one reverential mention after another of Annie Dillard and “Solar Eclipse,” her essay for The Atlantic that was collected in Teaching a Stone to Talk. Annie Dillard has an extraordinary mind and facility with English prose, but sometimes she wobbles off the path of acuity and leaves us in the wiggy weeds. I read her first sentence and thought uh-oh:

It had been like dying, that sliding down the mountain pass. It had been like the death of someone, irrational, that sliding down the mountain pass and into the region of dread. It was like slipping into fever, or falling down that hole in sleep from which you wake yourself whimpering.

If she was that unnerved by the driving into the Yakima Valley, what havoc might totality wreak?

It looked as though we had all gathered on hilltops to pray for the world on its last day.

Followed by:

My mind was going out; my eyes were receding the way galaxies recede to the rim of space.

(I must confess, in Connersville this was not my experience.)

The grass at our feet was wild barley. It was the wild einkorn wheat that grew on the hilly flanks of the Zagros Mountains, above the Euphrates valley, above the valley of the river we called River. We harvested the grass with stone sickles, I remember.

Oh, dear.

There was no world. We were the world’s dead people rotating and orbiting around and around, embedded in the planet’s crust, while the Earth rolled down.

And finally:

The event was over. Its devastation lay around about us. Seeing this black body was like seeing a mushroom cloud. The heart screeched. The meaning of the sight overwhelmed its fascination. It obliterated meaning itself.

She’d written more, but by that point I’d had enough.

I feel bad about have nothing profound of my own to offer here. I fancy myself a smart guy and skilled scribbler, but the Experience of Totality did not unhinge me (fortunately), nor did it summon deep thoughts about my place in creation or my oneness with the infinite or my connection to a gazillion generations of hominids. I didn’t even feel awe. What I felt was deep gratitude that I’d experienced this before I die. It was not, for me, a wellspring of limpid prose, but I don’t mind. I’m still deeply happy and thankful for those three minutes and forty seconds. That’s something, isn’t it?

And Annie Dillard did get one part right:

Now the sky to the west deepened to indigo, a color never seen. A dark sky usually loses color. This was a saturated, deep indigo, up in the air.

Next to sharing such a rare event with my beloved wife and friends, what lingered longest for me was the quality of the ambient light during totality. Yes, the temporary bullet hole in the sky was remarkable, but I’m a photographer and I could not get enough of the light bathing us and the trees and the grass and the stones. It was a blue I’d never seen and somehow had a granular quality.

I am not inclined to travel far in pursuit of the next Path of Totality. But I’d give something to see that light again.

Member discussion