Hey, is that wonder? No, over there, captive on the face of the obvious...

Letter No. 56: Includes dense but luminous prose, at least one hard-to-pronounce name, and reference to the “oh wow” school of nature writing.

Annie Dillard’s For the Time Being is a book simultaneously dense and luminous. That shouldn’t be possible except for a neutron star, but it is. It’s a 200-page meditation on small questions like, Why do we exist? Does one person matter? And where did everything come from?

She comes at these questions from multiple perspectives and invokes an array of philosophers and theologians and mystics and ordinary people observant and wise and patient with their own minds’ slow, painstaking process of finding order in the mess. She cites Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Isaac Luria, a neonatal care nurse, St. Augustine, Lawrence Kushner, some Osage Indians, the Talmud, Maimonides, and Jeremiah. She comes back to Teilhard again and again. He’s the headliner among a heavyweight supporting cast.

In her book, Dillard writes:

A man who struggles long to pray and study Torah will be able to discover the sparks of divine light in all of creation, in each solitary bush and grain and woman and man. And when he cleaves strenuously to God for many years he will be able to release the sparks, to unwrap and lift these particular shreds of holiness, and return them to God. This is the human task: to direct and channel the sparks’ return. This is tikkun, restoration.

You can’t just gloss that paragraph, which gives you an idea of what I meant by “dense.” If, like me, you don’t immediately cleave to people who spend their lives poring over Torah or any other scripture, try this: ignore the praying bit, and for “Torah” substitute “life” or “the universe,” and for “cleaves strenuously to God” substitute “pay attention.” Now Dillard’s passage reads like this:

A man who struggles long to study life or the universe will be able to discover the sparks of divine light in all of creation, in each solitary bush and grain and woman and man. And when he cleaves strenuously to this attention for many years he will be able to release the sparks, to unwrap and lift these particular shreds of holiness.

So, observe and study and think hard, and you might earn the good fortune to find wonder hidden in plain sight—what Dillard describes as “captive on the face of the obvious.” Why bother? Because all that exertion has a way of restoring the sparks of beauty and meaning in the world, and who couldn’t use more of that?

If this thinker I’m glibly conjuring here happens to be an artist, or at least is artful, so much the better. On a good day, good art simultaneously prompts Oh! Will you look at that! and Yes, yes, that’s what I feel, too. And now I know I’m not the only one. Wonder plus communion. A good day’s work.

For several years I had for a faculty colleague a fiction writer who, in my view, wielded a conventional mind and talent to write a string of mundane novels and short stories that got her tenure but not much else. We had attended a campus reading by Diane Ackerman, author of A Natural History of the Senses and The Moon by Whale Light. This colleague never missed a chance to disparage any woman writer who enjoyed greater acclaim or sold more books, which pretty much meant every woman writer ever invited to campus. Returning from Ackerman’s reading, my colleague snidely dismissed her as being “from that ‘oh wow’ school of nature writing.” I thought, How sad, to be so closed off from anyone who says, Look at the sparks! See ’em? What a pinched sensibility.

Dillard does not have a pinched sensibility. She possesses an astringent and sometimes edgy intelligence, and about the time she starts to sound like a barefoot seeker with a walking stick and an earthenware bowl, she scoffs at the idea of a spiritual path—at least the part about a path. Of those on spiritual quests she says:

Their life’s fine, impossible goal justifies the term “spiritual.” Nothing, however, can justify the term “path” for their bewildered and empty stumbling, this blackened vagabondage—except one thing: they don’t quit. They stick with it. Year after year they put one foot in front of the other, though they face nowhere. Year after year they find themselves still feeling with their fingers for lumps in the dark.

Which sounds a bit bleak. But she also says:

We live in all we seek…holiness lies spread and borne over the surface of time and stuff like color.

So which is it? The dark or the color? I think she means that so long as we believe we are on a path—what the witless these days insist on calling “my journey”—we are doomed to grope in the dark. But abandon the idea of there being any such thing as a path and you take a big step toward realizing that we don’t need a walkway to deep spirit because we already live in it. It’s out there. It’s everywhere.

For art, though, and perhaps for enlightenment, I think we may need both. That is, we may need the paradox of groping in the dark for what’s already in the light. Can there even be light without darkness? A physicist says yes, of course, but that’s physics, and it doesn’t change the artist’s reality, or the reality of anyone who labors to think through hard questions: to see the light, to see the color, we first have to grope in the dark. No dark, no light. No black, no color.

That millions of minds have described revelation or epiphany with the phrase “and then I saw the light” is no accident. Nor is the second syllable of “enlightenment.”

Got time for one more “if no x, then no y?” Surgeon and author Sherwin Nuland believes, “The brain has a way of evaluating what is best for the organism. And what is best for the organism is not just survival and reproduction, but beauty, an aesthetic sense.” He links this evolved attraction to beauty to something else going on in our heads: “I think that there is within the human organism, because of our cortex and our ability to process information—there is an awareness of the closeness of chaos.” What each of us considers beautiful will vary, but invariably at the heart of beauty is some kind of order. Not always apparent order, but order all the same. We are drawn to anything orderly because the chaos is always right there, on the other side of a flimsy barrier. We create beauty to hold it off. So: no chaos, no beauty. No chaos, no art.

We confer on artists the complimentary and flattering title “creators,” and they are in so far as they create paintings, stories, string quartets, poems, films, and dances that were not there before. But perhaps artists are also channels for what has already been created, for what’s there in plain sight but unseen and unacknowledged and unappreciated until an artist having a good day says, Hey, look at this. That new picture, it was always there, and the dance was always there and the story was always there. Just unnoticed until the artist waved his arms or raised her voice. Dillard says, “God decants the universe of time in a stream, and our best hope is to, by our own awareness, step into the stream and serve, empty as flumes, to keep it moving.” Our artists and our most eloquent thinkers work hard to keep creation flowing. They didn’t create the stream. But they shine light on the channel.

Or something like that. I think I’ll go for a walk.

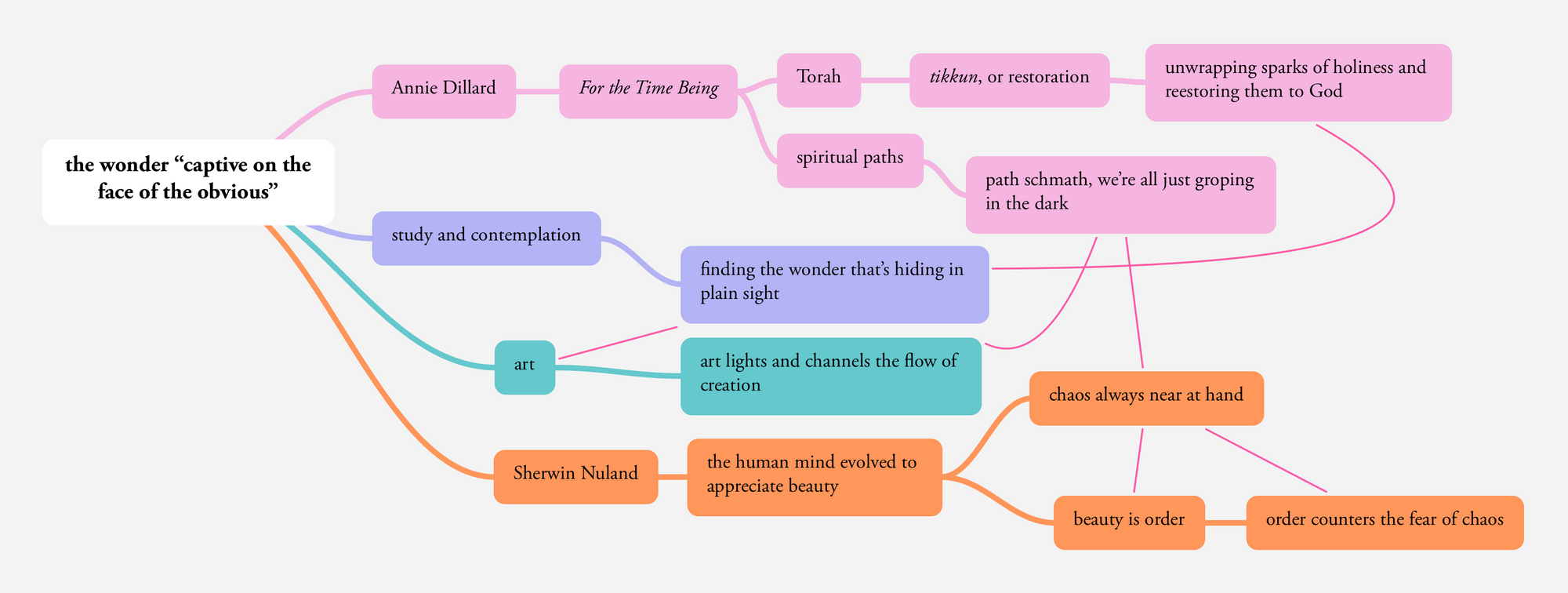

This letter’s mind map (click to enlarge if you’re reading on a browser):

Member discussion