Marooned on the way to school.

Or, on the bewitchment of color.

Dr Essai was an odd child. Solitary, imaginative, fond of walking by himself, arrested by moments that lodged in his memory like a pine sprout in a crevice. He preferred walking to school, a two-mile stroll he most enjoyed in the morning. About two-thirds of the way on his route, the doctor always looked forward to a house with white siding because it had a triangular bit of maroon, a decorative touch, up where the house’s end wall met the peak of the roof.

This wasn’t a nuanced, complex red that rewarded a long gaze. It was flat tint on a flat piece of aluminum siding. But every morning it was there and he’d stare at it for a long moment before moving on.

When he was maybe 12, he read a book about color psychology and the Lüscher color test. (The doctor was that sort of boy.) Max Lüscher, a Swiss psychotherapist, invented it in 1947. He believed that subjective color preference could be used to plumb the unconscious self that guided those preferences. The book came with a set of eight colored cards and instructions for administering a simplified version of the test. Dr Essai thought it would be interesting to test his father, who had trained as a painter. He placed two cards before his dad and asked him to pick the one he preferred.

"Neither," his father said.

"Dad, it can't be neither. Everybody prefers one color over another. Everybody has favorites."

"No, I have no preference."

"That's just weird. Why not?"

"Because when I look at this blue or this green or this brown, I don't see color, I see possibility. I see what might happen if I put this one next to this one, or that one on top of the other. They could all be useful."

"Forget it."

Gazing at the maroon piece of siding during the pause on his walk to school, Essai as a boy liked feeling that no one else anywhere saw it like he did, not even whoever lived in the house. Without being able to articulate it, he saw possibility.

If you are bewitched by color, every glance out the window, every walk down the street, rewards. Driving to the grocery store this morning, the doctor approached a set of rowhouses in Baltimore and pulled over. He didn't have his camera but he had his iPhone, which he'd recently heard a professional photographer call "a great camera that makes crappy calls." He could not resist that pink-verging-on-salmon house with the aqua door. The chartreuse Jeep parked on the street was a bonus.

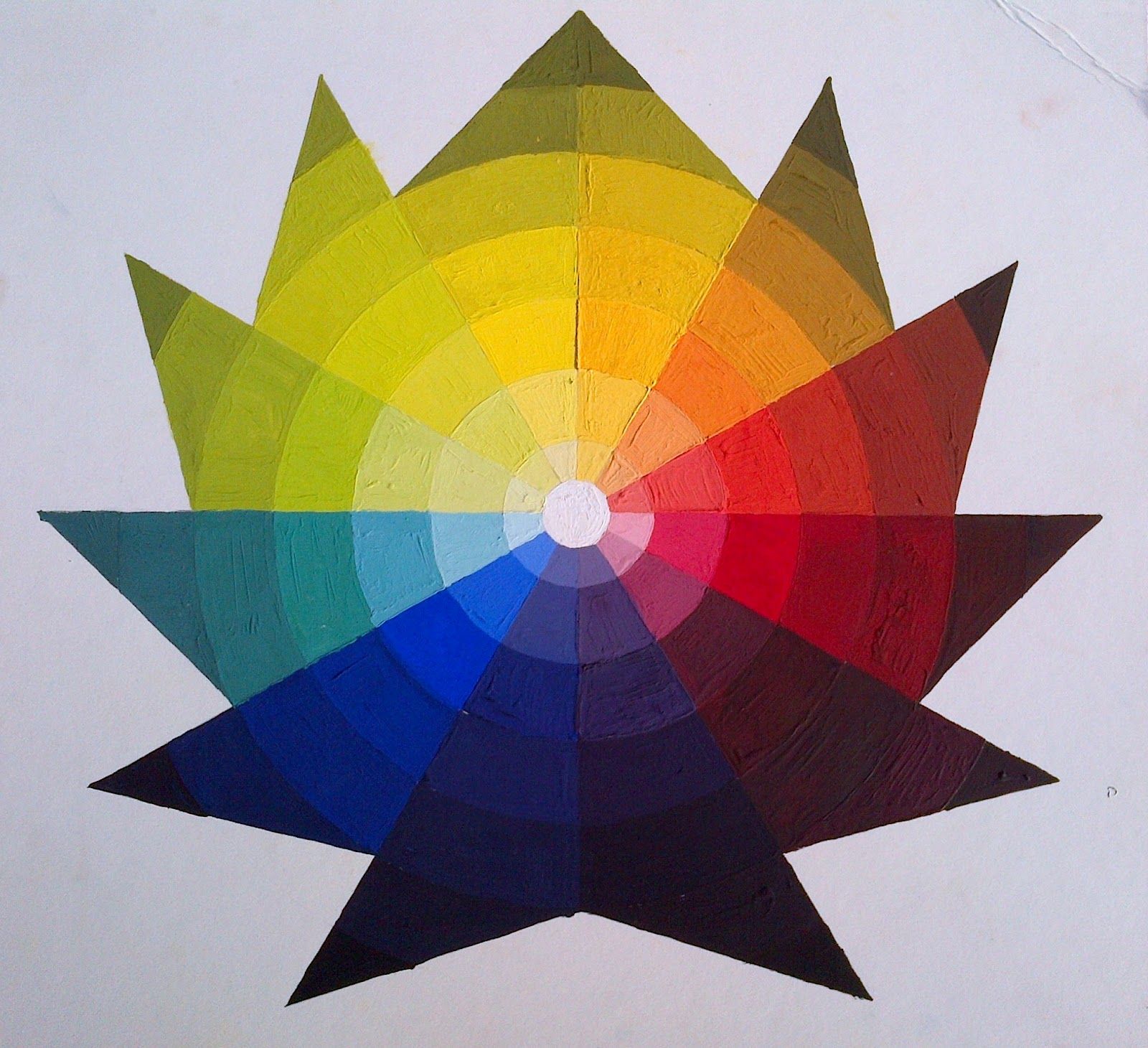

Whoever was in charge of painting this house saw possibility. On a block with a yellow, a green, a white, and two brick houses, why not coral pink or whatever the paint company called it? And then the door. The safe, banal thing would be white. But someone was paying attention. Someone was alert to color theory and complementarity. Thinkers back to Newton and Goethe have pondered what can be learned if colors are arranged in certain ways. There's the spectral circle, Delacroix' triangle, Charles Blanc's color star. Albert Munsell came up with another circle, as did Wilhelm Ostwald. George Field put things in a line, Munsell moved on from his circle to a three-dimensional tree, and Johannes Itten created a lovely star that would look dangerous were it not so pretty.

With all these wheels and stars, colors that appeared opposite each other looked good together — they complemented each other and this was noticed. And were you to look up the complement to the pink/coral/salmon on the rowhouse's exterior, you'd find the blue of this door. (A close match even appears on pg. 133 of the 50th anniversary edition of Josef Albers's profound Interactions of Color.)

Somebody had the wit to see the possibilities here and the verve to realize them. Dr Essai snapped a photo, took in all the colors once more, remembered the boy gazing at the maroon triangle, and drove off happy.

Member discussion