On Christopher Columbus's diary

Or, somebody's mom just threw out history

When wind and current and vague navigation brought Cristoforo Colombo to the shores of Haiti in 1492 — Yippee! I have found a westward passage to the Indies! I’m gonna be rich! — he kept a diary. A valued document, one should think. Yet it disappeared, though not before a Dominican friar named Bartolomé de Las Casas had his abstract of the diary copied in the 1530s. The good friar’s scrivenings seemed lost, as well, until around 1790 when, in the words of historian Jill Lepore, “an old sailor found it in the library of a Spanish duke.” As one does.

The “old sailor” was the magnificently named Martín Fernández de Navarrete y Ximénez de Tejada, and he was more prominent in his day than Lepore’s designation might suggest. A senator, a historian, a knight of the Order of Malta. The duke was the Duke of the Infantado, should anyone ask.

The original Journal of the First Voyage might still exist. Queen Isabella I had it copied, and, behaving like a queen, kept the original and returned to Colombo a copy. The original has not been seen since 1504, but someone should do a serious check of ducal libraries, because leaves of torn parchment that might have been from the original — Colombo’s signature appeared on one bit, as did the date 1492 and a crude map of Hispaniola — were sold to the Duchess of Berwick and Alba by the widow of the librarian to the Duke of Ossuna in 1894. The widow then disappeared. So did the parchment. No word on the duchess.

All of this arose because at some point Colombo/Columbus mislaid his copy, or lent it to someone who never gave it back (never lend books), or dropped it overboard on another voyage; or, most likely of all, it found its way to his grandson, Luis, who sold it, in the words of historian Barry Ife, “in order to subsidize his legendary debauchery.” The scholar Samuel Eliot Morison, writing in a 1939 edition of The Hispanic American Historical Review, seemed convinced that whatever the duchess of Berwick and Alba bought was legitimate. He was not charitable toward the widow:

It seems probable that her husband had stolen it from the Ducque de Ossuna’s library, and that she, being ignorant and illiterate, tore out the part including the map to sell as a “picture,” and destroyed the rest.

Hmmmrrrfff. Elitist.

Dr Essai questions how Samuel Eliot Morison knew any of that, but never mind. He loves these stories that demonstrate the raggedy, patchy nature of history. An entire esteemed discipline of the humanities depends on someone taking notes, someone saving correspondence, someone creating an archive or a library, something turning up at an estate sale or in a manor’s attic or a duke’s book nook. History loses when someone makes heedless use of irreplaceable documents as foolscap or fishwrap or ballast.

The doctor has just embarked on Dr. Lepore’s substantial These Truths: A History of the United States. On pg. 4, she writes:

Most of what once existed is gone. Flesh decays, wood rots, walls fall, books burn. Nature takes one toll, malice another. History is the study of what remains, what’s left behind, which can be almost anything, so long as it survives the ravages of time and war: letters, diaries, DNA, gravestones, coins, television broadcasts, paintings, DVDs, viruses, abandoned Facebook pages, the transcripts of congressional hearings, the ruins of buildings. … But most of what historians study survives because it was purposely kept — placed in a box and carried up to an attic, shelved in a library, stored in a museum, photographed or recorded, downloaded to a server…

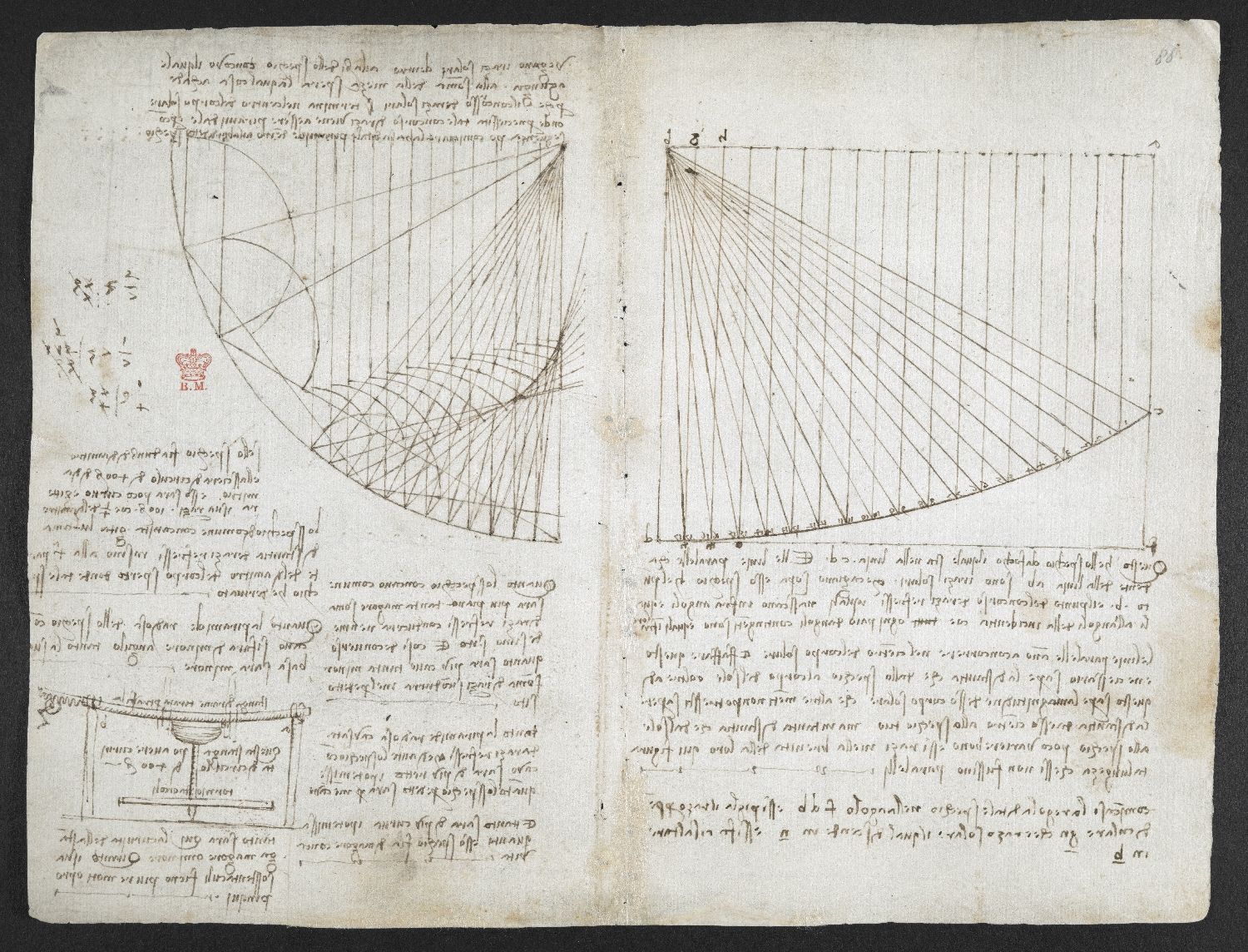

Ptolemy II and Ptolemy III assemble the great library of Alexandria, and a dickhead like Julius Caesar accidentally burns it down (far from the whole story of the library’s decline and dubious in its own right, but too good a tale to pass up). Fascists and zealots burn books. An ailing 17th-century baron burns a trove of historically valuable letters because, if he doesn’t, his wife will learn he’d been canoodling with an orange-seller. Slander and calumny enter the historical record through being repeated often enough. Someone with a sketchy grasp of an indigenous language writes the “history” of a tribe from interviews with bemused indigenes who quickly grasp the value of telling anthros whatever they want to hear. Leonardo’s stepmother throws out his adolescent notebook and doesn’t want any lip from him. “Yes, I threw it out, it was moldy and smelled bad and we don’t need any more clutter in this house. Stop complaining and do your homework. Your grades could be better, young man.”

From this dog’s breakfast of a record we tell and retell the story of our time on this earth, sifting and recasting patchy evidence, recreating memories every time we recall them, which is what our brains do with their own stored memories.

The doctor once chatted with writer Lawrence Weschler, author of numerous books and pieces for The New Yorker. Weschler was skeptical about some of the conventional distinctions between fiction and nonfiction. He argued that when a writer organizes facts and knowledge as a story, that is a literary process that produces maybe not fiction but a literary simulacrum of reality that should never be mistaken for the real thing or the final word. Interviewed by Bob Garfield for the radio program On the Media, Weschler said,

I would start out by asking you is anybody ever not making stuff up? When you pick up the newspaper and read about a news conference, let's say, somebody went to that news conference. You are not reading the entire transcript. … You are relying on the reporter to select the important things and to put them in a particular order. You are assuming that his editor has gone and reshaped those things. That is all fictional activity, in the sense that it is composing, it is making up a world.

The world, the universe, is not a story. Story is how our roiled minds create order out of disorder so we can rise from bed and take on the new day with what feels like agency. Physicist Brian Greene will tell you that we have no real agency, that everything, everything, has been determined by the laws and flow of particle physics. Digital physicists look at the same universe and see computer code — everything we do is dictated by what we might call the God Code, and we’ve no way of ever proving that’s not the case, which must come in handy when dealing with peer review. Many people believe history weighs heavily on our present lives, imposing constraints, setting parameters, coloring how we regard our society and culture and polis, not to mention our imagination of the possible.

It feels true, this idea that the past asserts itself in our present. T.K. Whipple wrote in Study Out The Land: “All America lies at the end of the wilderness road, and our past is not a dead past, but still lives in us. Our forefathers had civilization inside themselves, the wild outside. We live in this civilization they created, but within us the wilderness still lingers. What they dreamed, we live, and what they lived, we dream.” All the more important, then, that we approach reading history with the right frame of mind and never forget that we create our cultural biographies out of the haphazard preservation of random material. For all we know, there were 12 Commandments and some disgruntled ancient copyist ran out of papyrus after the first ten and thought, Whatever.

“History is the study of what remains.”

Member discussion