An addendum to what the gods do not confer

Or, there's always one more thing

A week ago, Dr Essai scribed a letter with the cumbersome title “What Does Not Cometh from the Gods.” He had been mulling over talent, rejecting the idea that it was a mystical gift bestowed by the universe in favor of the mundane notion that it is a personality trait. Unromantic and uninspiring, but in the doctor’s view more likely to be the case.

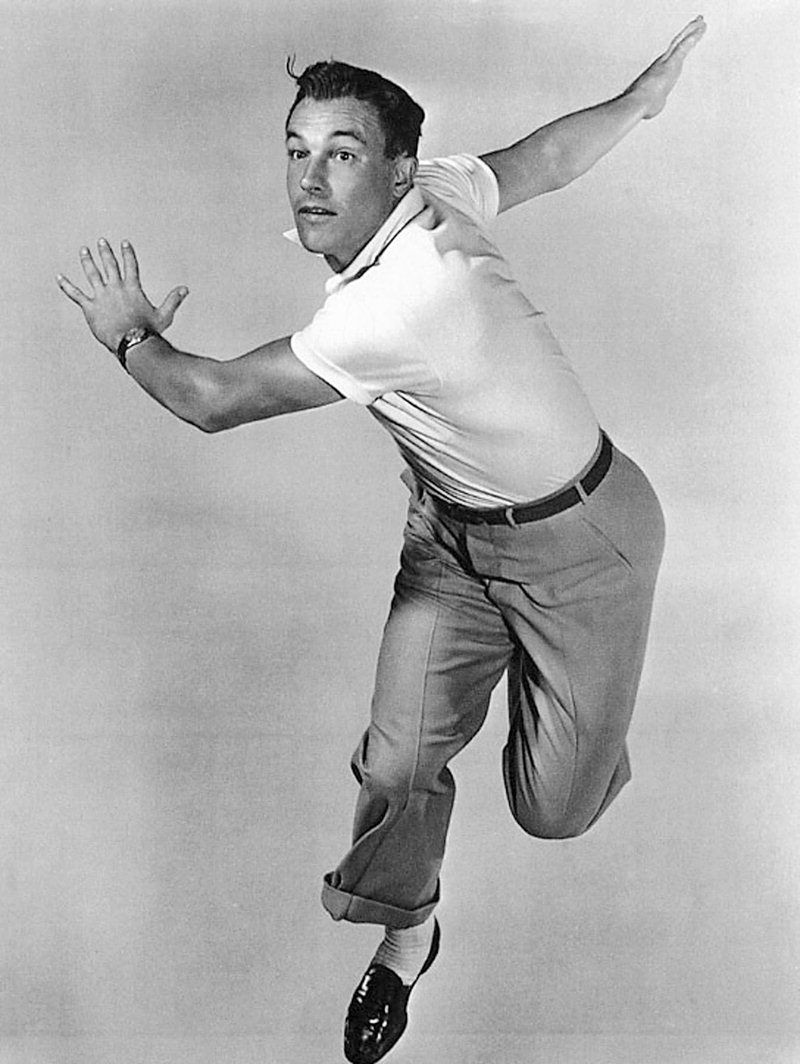

Seth Godin, the able scribbler and podcaster who has written 20 or so books, founded the online AltMBA program, and created the excellent Akimbo podcast, recently rebroadcast a 2018 episode of the latter titled “Genius.” The doctor was pleased to hear how much Mr. Godin’s thoughts on that topic aligned with his own on talent and creativity. But what stuck with him, oddly, was a brief audio clip of Gene Kelly tap dancing.

The sound produced by the dancer’s nimble feet prompted the doctor to think about an addendum to his notes on talent, a corollary regarding creativity. In his essay on talent, he wrote, “Dr Essai has observed time and again how the finest artists are the ones whose idea of fun is spending hour after hour, day after day doing the same thing over and over and over and over. And then some more. … The essential personality quirk could be described as nothing more than being endlessly fascinated and pleased by the repetitive tasks that make art.”

Upon listening to Seth Godin and Mr. Kelly’s feet, the doctor realized that he’d left out an essential aspect of creative artistry. Accomplishment in the arts still requires that crucial fondness for uncounted hours spent alone making, through the smallest of incremental steps, something that may or may not turn out to be art. But that odd predisposition to investing one’s only life in a creative practice needs one more trait to bring forth the sort of work that perturbs the orbit of an art form and sets it on a new course.

Dr Essai does not have a handy catchphrase or neologism for this trait. To get at what he’s trying to say, he must return to Gene Kelly. Kelly moved as a dancer, with and without tap shoes, in ways no one had seen before, dance that was simultaneously familiar and novel and always seemed exactly right and unique to him. He was a dance genius. But if we reject the idea that his genius had been mysteriously zapped into him like some sort of dance neutrino, where did his new moves come from?

They came from the practice studio. They came from him dancing, dancing, dancing, tap, tap, tap, applying himself to get better at what he thought he didn’t do well enough, when by chance he did something in practice that he hadn’t done before, a move that took him, and dance, somewhere it hadn’t been. And here is where the second essential personality trait enters the story. Traits, actually, for the doctor believes there are two. First is the crucial awareness: Hmmm…I haven’t done that move before, and it’s interesting, it’s something I might do more with. Second was a trait more essential than the awareness — the curiosity, drive, and willingness to see where that new move might take him and might take dance. It might well take him nowhere. Nobody knows dead-end streets like an artist. But he had to know.

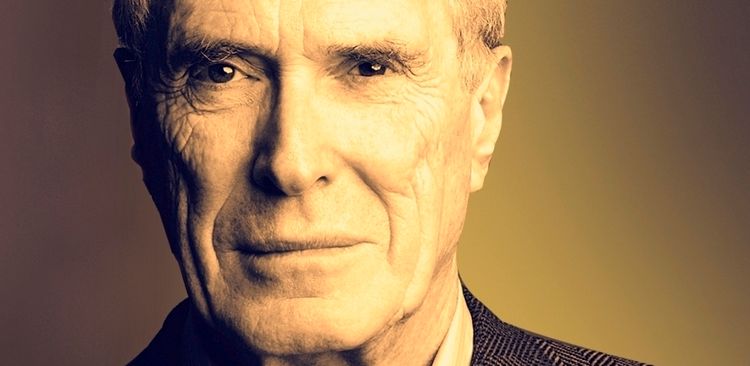

By this point Gene Kelly could have settled for doing what his adoring public expected — dancing like Gene Kelly for the remaining years of his career. But he didn’t. His personality wouldn’t let that new move go unexplored. By the time Picasso began fooling around with cubism, he was Picasso. He had a lot on the line when he stopped producing the canvases that had fostered a growing reputation and started making paintings that struck many people as not even art, all because he wanted to know what might come out of fracturing the visual plane. Bob Dylan turned away from folk music, which had made him an international star, because he wanted to rock, and then when he wanted to sing Christian music in the 1970s, he did that, and then he moved on to his rich later work, because it was not in his personality to coast. Messing around at the typewriter, at the piano, with his guitar, in the studio, he heard new things and let them guide him to new work unlike his old work. If his fans disapproved, that was their problem. They were more comfortable with an entertainer but he was an artist.

Lesser artists may be aware that they’ve glimpsed a new line of inquiry, a new way to do their art, but they don’t follow through. They lack the courage, perhaps, and there's no shame in that. Art is fucking hard and jeopardizing whatever success you've achieved, be it critical or commercial or among a dozen of your friends, is a daunting prospect. Some artists achieve remarkable levels of craftsmanship but never have the vision to go off the map. Some can't bring themselves to be a sufficient pain in the ass. And some artists simply lack interest in striking out for the territory ahead. They turn out to be Joan Baez, not Bob Dylan. It's their life and their practice and they should do whatever they want with their one lap.

So what might the term for this additional personality trait be? Dr Essai doesn’t know. Creative cussedness? No matter. Call it whatever you wish. And if you’re an artist, do all you can to cultivate it.

This letter refers to a previous letter that may be found here.

Member discussion