If you already know what “opsimath” means you can skip this one

Or, okay, word nerd, stop showing off and read the letter

Dr Essai does not know much about M.F. Corwin. He seems to read a great many books. He reviewed one as “perhaps five pages of ideas lightly spread throughout a two hundred–page book,” which is well penned. For 22 years he has sporadically attended to an enigmatic blog titled An Eudæmonist. Last month, the eudæmonistic Mr. Corwin offered this:

One encounters so many interesting words while reading, some of which are unfamiliar, some of which – though tantalizing – send one to the dictionary immediately, and some of which linger in the mind even if already known. I used to gather such things elsewhere in bits and pieces, but it seems amusing to collect them together for the nonce:

mirativity · gracile · atrabilious · balanophagy · quern · pericarp · rheology · penitentiarization · exsufflicate · flocculability · darnel · guimp · pilulous · acceptation · dissentient · faunistic · squamation · oeillade · pretermit · tensity · epigone · scatterlings · surquedrie · usufruct · fugacious · allolalia · omnium-gatherum · extensity · protreptic · sone · coapt · abscissa · pablum · nosological · periclitate · covin · quoin · flagitious · agglutination · rubbisheries · nidification · spiderling · amaroidal · labile · ritornello · whiffler · apricity · nimbed · clinquant · keech · chatoyant · entrepôt · originary · spathe · briseable · fume · imbrication · matagrabolize · tabagie · chriae · paraclete · ancilla · spalling · formication · roquelaure · atelic · crypsis · entitativity · flench · homoscedasticity · imbricated · mignardise · phasic · pretermit · propaedeutic · recalcitration · acervation · amaranthine · asperity · coign · contredance · dislodgement · muculent · noetic · pleat · scission · theopathic · transpicuous.

So you know, “balanophagy” is the practice of eating acorns; “guimp” is a type of upholstery trim; “mignardise” is an affectation of delicacy; a “whiffler” is one who frequently changes opinions; and “muculent” means slimy. Yum.

Like the Eudæmonist, the doctor frequently comes upon obscure and obsolete words in his eclectic reading. One such word is “opsimath,” cited by The Oxford English Dictionary as first appearing in print in 1883 in The Times of London and defined as “one who begins to study or learn late in life.” Not to be confused, OED warns, with opsomania, “A morbid longing for dainties, or for some particular food.” Noted.

Dr Essai would never consider himself opsomanic. He finds it impossible to imagine any longing for food as morbid. But he does fancy the idea of being an opsimath. To accept that does require some squinting and a tolerance for imprecision. The doctor began to study at age 6 when he commenced reading and has not let up in the ensuing 63 years. But when did he begin to learn? That’s a trickier question.

One could assert that Dr E never learns. Mean but not inaccurate. He would benefit from dropping 15 pounds, yet remains steadfast in his belief that there are no calories in gin. He is sure that any day now the cats will stop vomiting kibble minutes after ingestion. He thinks surely there must be a bottom to Marjorie Taylor Greene’s deep well of stupidity. One can only sigh.

During 50 years of scribbling for pay, the doctor has learned much about stringing together sentences. Yet time and again he stops on a paragraph from an admirable book and reads it twice more and thinks, You can do that? I didn’t know you can do that. I don’t even know how to do that. He appreciates Stanley Fish’s appreciation of a sentence and acknowledges with dismay, I could have read that same sentence a dozen times and never noticed what was going on there. How can I have been writing for a half-century and still not know how to read? He learns that a packrat’s nest sometimes includes pieces of bone, and that as part of its construction the rat urinates on the nest, and that the urine hardens into something that resembles amber, thus preserving some nests for millennia, preserving them so well that modern paleoecologist can study bone fragments and trapped insects from unearthed ancient nests to learn about animals that lived in other eras. All thanks to packrat piss. How did the doctor pass through so many decades of life not learning that?

There are things that should never be learned, like barbershop quartet singing and Caribbean steel drumming. There are some things one should learn as late as possible. The unfathomable loss of someone beloved who has died is forced learning that no one should have to deal with until at least age 50. But life is not so considerate.

Some learning cannot be rushed. Dr Essai may doubt his acuity as a reader on occasion but does know enough to believe that hundreds of profound books are wasted on anyone younger than 35, if not older. It’s pointless to make a 17-year-old grind through Antigone or The Odyssey or The Scarlet Letter or The Color Purple. Exposing children to fine literature will not make them better people — Stalin had a huge library. Nor will it launch them on a lifetime of avid close reading. A forced march through Macbeth is as likely to put a kid off reading. It’s hard to impart learning if you can’t first spark enthusiasm. Imagine even a smart teenager forced to read Pilgrim’s Progress who then thinks Yeah, gimme some more of that.

The doctor fancies himself an opsimath not because he got a late start, which is the connotation of the word, but because he now wants to understand things that take 70 years of life to fathom, 70 years of intellectual crop rotation and the incremental business of learning to read and learning to think and learning to learn. The wise man and the wiseass alike can be knocked off stride when the mist clears and they see false assumptions of knowledge and understanding with dismaying clarity, but the smart one sees opportunity: Finally, questions worth the mind I’ve clabbered together. First day of class.

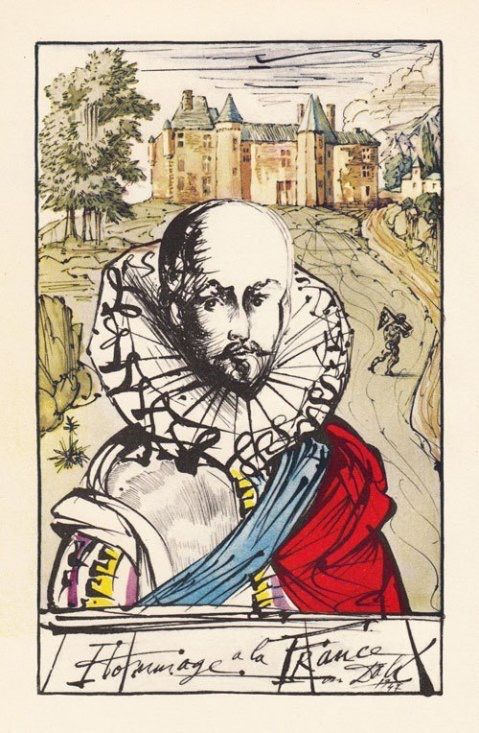

Montaigne looked at his life and thought, Que sais-je? — What do I know? In those three French words the doctor hears three questions. One, taking stock: What do I know that I can apply to this new mystery? Two, skeptical self-awareness: What do I know, and how much of what I believe is wrong? And three, candor about his mind’s limits: Eh, in the end, what do I know, anyway?

In 1974, the comedy troupe Firesign Theater issued an album titled Everything You Know Is Wrong. Inscribe that on a beam in your study. Call it the opsimath’s credo.

Member discussion