Lamb’s head and pluck—it’s what’s for dinner

An ordinary by the name of City Tavern opened in 1773 at the intersection of Walnut and Second streets in Philadelphia. According to food historian Victoria Flexner, it was bankrolled by “a group of wealthy Philadelphians who’d decided there was no place in town that met their standards for decent food and drink.” When John Adams pulled into town on August 29, 1774 for the First Continental Congress, he was tired and dirty but went straight to the tavern for dinner. Thomas Jefferson took most of his meals there as he drafted the Declaration of Independence. When members of Congress needed somewhere to celebrate the second Independence Day on July 4, 1777, they selected City Tavern.

In the November 2025 issue of The Atlantic, Flexner published an article, “We Hold These Turkeys to be Delicious.” From diary entries, letters, and other documents, she reconstructed a plausible menu for that July 4 celebration.

A customary first course would have been soup: perhaps turtle soup, with meat from green sea turtles simmered in veal broth enhanced by splashes of imported sherry or Madeira; or pepper-pot soup from the West Indies, devised by slaves on Caribbean sugar plantations who yearned for West African callaloo and did their best to recreate it with ingredients at hand in Jamaica or Barbados. To the slaves’ receipt, Philadelphians might well have added Asian spices like mace and cloves, and possibly beef and pork, meats introduced to North America by Europeans.

There would have been fish, including sturgeon from the Delaware River. A variety of game such as deer, turkey, rabbit, and pigeon, pheasant, woodcock, snipe, and duck. Cooks would have roasted them in a hearth, as they had for centuries in Europe. On the side, summer squash, cucumbers, peas, and potatoes, the latter native to Peru and a European staple by this time. Desserts might have been spiced with nutmeg from Indonesia, cinnamon from Sri Lanka, or ginger from the Caribbean. And there would have been apple pie, that quintessential American dish, possible only because apples traveled from Central Asia to Europe in the 16th century before crossing the Atlantic.

Oh, and as darkness fell, we know from records that there were fireworks. A Chinese invention.

A year after defiantly declaring ourselves to be our own nation, some of our founders tucked into meals that told a story: before our infant country even had a name it was inextricably enmeshed in global culture and the global economy. Nobody coined the politico-economic term “globalism” until 1941, but through trade, in 1777 the colonial foodshed spanned the world. At City Tavern, the American melting pot was not a metaphor. It was in the hearth, suspended over a wood fire.

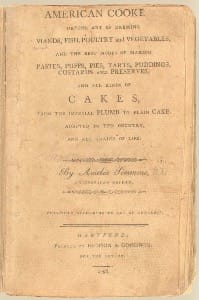

For decades cooks in the colonies relied on English cookbooks. The first American-made kitchen manual, as far as we know, was American Cookery. It appeared in 1796 written by Amelia Simmons, “an American orphan” (as the cover tells us). The book’s 47 pages included receipts for “Calves Head Dressed Turtle Fashion,” “Soup, of Lamb’s Head and Pluck,” “Fowl Smothered in Oysters,” “Tongue Pie,” and “Foot Pie.”

Mysteries abound.

I began reading the calve’s head instructions with no idea what “dressed turtle fashion” means and ended up no wiser. But my labors were rewarded with this pungent instruction: “chop the brains fine and stir into the whole mess in the pot.” Sounds like a weekly team meeting.

Smothering a fowl in oysters seemed straightforward:

Fill the bird with dry Oysters, and sew up and boil in water just sufficient to cover the bird, salt and season to your taste—when done tender, put into a deep dish and pour over it a pint of stewed oysters, well buttered and peppered, garnish a turkey with sprigs of parsley or leaves of celery; a fowl is best with a parsley sauce.

Not sure what to make of “dry Oysters”—toweled off, perhaps?—but peppery well-buttered stewed oysters sounds delicious.

“Soup, of Lamb’s Head and Pluck” baffled me until I tracked down a definition of that last word. In the 18th century, “pluck” was a general term for organs, in this case heart and “lights,” which are lungs. (Yum. “Pluck” because the cook plucked them out of the carcass? I dunno.) The receipt in the second printing of the book listed “potatoes, carrots, onions, parsley, and fummerfavory.” Mrrmmff? Then I recalled that typesetters of the day frequently used a so-called long S that resembles an F—so, “summersavory.” Sounds delicious—it’s an herb—but I prefer fummerfavory.

And then the last two dishes. Tongue pie was about what I’d imagined: beef tongue plus sugar, butter, apples, currants, cinnamon, mace, and a pint of wine, which I might need to drink before digging into a slice. And “Foot Pie”? That one was a mincemeat pie. The feet came from cattle. Here is the American orphan’s receipt in full, faithful to the original punctuation, grammar, and syntax:

Scald neet’s feet [that is, cow’s feet] and clean well, (grass fed are best) put them in a large vessel of cold water, which change daily during a week, then boil the feet until tender, and take away the bones, when cold, chop fine, to every four pound minced meat—add one pound of beef suet, and 4 pound apples raw, and a little salt, chop all together very fine, add one quart of wine, two pounds of stoned raisins, one ounce of cinnamon, one ounce mace, and sweeten to your taste; make use of paste No. 3—bake three quarters of an hour.

As with tongue pie, I’d need as much wine in me as in the dish. Can’t imagine eating this unless I were one stoned raisin.

As for “paste No. 3,” that was flour and butter and “whites of egg.”

The late anthropologist Sydney Mintz used to argue there was no such thing as American cuisine. I knew Syd at Johns Hopkins University and wrote about him in 1998. From the published story:

Lest culinary patriots think he singles out Americans, Mintz says there’s no genuine French, Italian, or Chinese cooking, either. There’s what restaurants and cookbook authors label French cooking, etc., but Mintz says that has more to do with marketing than cookery. The only authentic cuisines, by his definition, are regional. One can speak properly of Bavarian cuisine, but not German; Szechuan cuisine, but not Chinese; Alsatian oui, French non. He concedes that a case can be made for American regional cuisines such as Southwest or New England, but he fears not for long. He thinks they’re endangered species, threatened by the American love of novelty, homogeneity, and convenience, and by the food industry that caters to it.

… Mintz believes that Americans don’t have the same deep involvement with food as do people from the various regions of France or Italy, for example, people who in his view truly understand cuisine. When Mintz uses that word, he means cooking that has developed over centuries of preparing, by traditional methods, whatever was near-at-hand. He says, “I mean both the system of foods eaten by people in a region, and the way they share a dialogue with each other about what they are eating.” This is why, in his view, all genuine cuisines are regional. They rely on the products of local agriculture and food gathering. They follow the seasons, using fresh ingredients as they become available throughout the year.

I’d suggest that much of what’s on the 47 pages of American Cookery meets Syd’s criteria halfway. Colonial cooks relied on what was seasonally available and near at hand. They were locavores—except for the mace and cinnamon and cloves and Madeira.

The image of John Adams or John Hancock or Samuel Adams dabbing his mouth with a napkin in a colonial Philadelphia tavern after working through turtle soup, sturgeon, roast turkey, potatoes, and apple pie could not feel more American. The insipid patriotic picture paints itself. But the meal was a convergence of American river and forest; English foodways; the desperate lives of West Indian slaves; and ingredients spread by traders from Peru, Ceylon, the Moluccas, Kazakhstan, Jamaica, the Gold Coast, and Portugal. It was the product of more than two centuries of global trade and the restless nature of people, ideas, and goods. And the pleasures of the table.

Please pass the fummerfavory.

Coda

- Before it appeared in my book, The Man Who Signed the City, my story on Sydney Mintz, “Matters of Taste,” was published by Johns Hopkins Magazine. You will find it here.

- Reading American Cookery set Dr Essai on a winding path through old cooking manuals. There will be more to come in the following weeks. The doctor knows a rich vein when he sees one.

It’s just not easy feeding oneself in this economy. Have you priced neet’s feet, beef lights, or fummerfavory lately? It’s appalling. You could help fund Dr Essai’s next tongue pie by becoming a voluntary paid subscriber. As always, thank you so much for being a Joggler.

Member discussion