When You’re Done Here, Read Some E.B. White, But Not “The Elements of Style”

Includes some literary name-dropping, references to Shakers and weasels, and consideration of arteriosclerosis in turtles.

The writing life has its commonplaces, in common with the pursuit of any art: modest income; little public recognition; the widespread assumption that anyone can do it (How hard can it be—seriously, my kid could do that!); venal, witless hacks who control most of the resources; and a stream of books that promise to reveal the secrets and techniques that will transform any floundering scribbler into a literary artist.

This morning, a scan of my bookshelves turned up more than 30 of these books. Their authors include John McPhee, Annie Dillard, George Saunders, Ursula K. Le Guin, Phillip Lopate, Ray Bradbury, Vivian Gornick, and Kurt Vonnegut Jr. Some are little more than plumped-up guides to grammar and syntax. Some concentrate on making the aspiring scribbler a more astute reader. I value some for the elegance of their prose: the McPhee (Draft No. 4), Alice McDermott’s What About the Baby?, The Writing Life by Annie Dillard. But only two have had any lasting influence on me as an artist—the Dillard and Phillip Pullman’s Dæmon Voices. The rest? Eh. As editor John E. McIntyre astringently observed in Bad Advice, “Advice on writing in general is marred by oversimplifications, half-heard advice, and idiosyncratic preferences—sometimes bizarre—passed off as professionalism.”

Which brings me to another commonplace of the writing life: the imperative to study Strunk & White’s The Elements of Style. Of all the how-to volumes on my shelves, none is as commonly assigned as Strunk & White. (That’s how those of us in the word biz always refer to the book, never by its title. If you want to sound like a seasoned pro, take note.) Teachers, editors, writers, and wannabes on social media all reflexively nudge the book across the table toward the aspirant. My favorite example of this was Dorothy Parker, who wrote, “If you have any young friends who aspire to become writers, the second-greatest favor you can do them is to present them with copies of The Elements of Style. The first-greatest, of course, is to shoot them now, while they’re happy.”

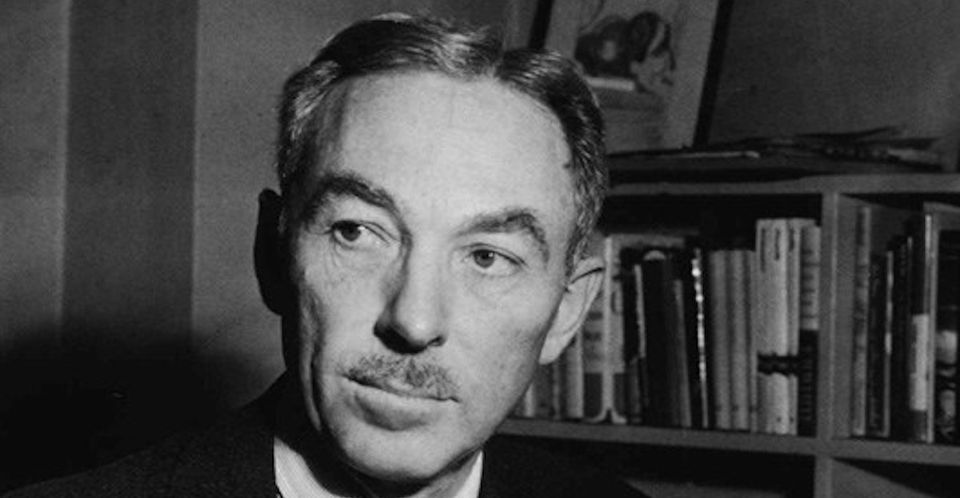

The endurance of this slender mash-up of a book puzzles me. It began life in 1918 as a brief grammar, vocabulary, and spelling guide by William Strunk Jr., who had a knack for being wrong about grammar. Forty years later, E.B. White, who had been Strunk’s student, beefed it up to something that could be sold as a real book by jotting down his thoughts on how best to write well. In 1959, the expanded book’s first year, Macmillan sold an astonishing two million copies.

Not for the quality of its instruction. Strunk & White is fine for a 14-year-old struggling to write an essay for English class. It will do no lasting harm. But if you want to write anything more sophisticated than homework, The Elements of Style will be of little help.

If you’ve read as many of these books as I have, you will not be surprised that E.B. White’s advice on how to write well can be summarized as “write like E.B. White.” As an exemplar you could do far worse than Mr. White. He was a splendid writer but he could be cranky when dispensing literary opinion. In The Elements of Style he wrote, “Rich, ornate prose is hard to digest, generally unwholesome, and sometimes nauseating.” Okay, but only when it’s bad rich, ornate prose. The heart of White’s diktat—keep it simple, keep it clear, keep it brief—plays to a bias against artistry that has long been an aspect of American culture. Real Americans suspect artists and revere craftsmen. I too revere craftsmen, but I don’t confuse them with artists. Were I ever to buy a custom house, I’d have it built by craftsmen but designed by artists. The two may overlap but they are much different. To argue that the best English must consist of lean sentences made from short, plain Anglo-Saxon words, and not too many of either one, not only privileges elementary craftsmanship over artistry, it’s just silly. If you’re giving me directions to your house, then sure, keep it Strunk & Whitish. If you’re trying to make literary art, don’t listen to grumps who seem to think that Joseph Conrad would have been better off had he written stories like the Shakers built chairs.

Strunk & White gets credit for campaigning against flaccid prose. That’s fine, as far as it goes. But the true problem with bad writing is rarely flaccid prose. It’s flaccid thinking. Overwrought sentences often are employed to disguise underwrought reasoning, but excising clichés, freeloading adjectives, and a few weaselish qualifiers might tighten the prose but it won’t resolve woozy thinking. Strunk & White can’t fix stupid. Nor can it impart artistry.

What matters in fine writing is not words spelled right and in the proper order. That’s merely the starting point. What matters is intelligence, knowledge, practice, intention, and taste. The best advice from writers, even great ones, isn’t found in their writing manuals. It’s in their best novels and essays and stories and works of reportage and scholarship. You become a great writer by writing all the time and studying the great books that resonate with you intellectually and emotionally. A working knowledge of grammar and syntax plus a good eye for basic mistakes in your own work is essential, but if that’s all you’ve got you won’t get far.

Can you learn from E.B. White? Oh lord, can you ever. But the education is in his essays. A plain style worked for him, as did brevity, not because that’s the only way to write, but because that’s the only way E.B. White could be the extraordinary artist he was. Were I to try it, I wouldn’t become America’s next great essayist, I’d just be some guy scribbling pallid imitations of E.B. White. If you study him in search of a declaration—This is how it’s done.—you will miss the point. Read him for the countless times you will find yourself asking, as a writer, How did he do that?

Here I turn things over to the master. This is E.B. White’s “A Turtle’s Life,” published in 1953 by The New Yorker, in its entirety:

We strolled up to Hunter College the other evening for a meeting of the New York Zoological Society. Saw movies of grizzly cubs, learned the four methods of locomotion of snakes, and were told that the Society has established a turtle blood bank. Medical men, it seems, are interested in turtle blood, because turtles don’t suffer from arteriosclerosis in old age. The doctors are wondering whether there is some special property of turtle blood that prevents the arteries from hardening. It could be, of course. But there is also the possibility that a turtle’s blood vessels stay in nice shape because of the way turtles conduct their lives. Turtles rarely pass up a chance to relax in the sun on a partly submerged log. No two turtles ever lunched together with the idea of promoting anything. No turtle ever went around complaining that there is no profit in book publishing except from the subsidiary rights. Turtles do not work day and night to perfect explosive devices that wipe out Pacific islands and eventually render turtles sterile. Turtles never use the word “implementation” or the phrases “hard core” and “in the last analysis.” No turtle ever rang another turtle back on the phone. In the last analysis, a turtle, although lacking know-how, knows how to live. A turtle, by its admirable habits, gets to the hard core of life. That may be why its arteries are so soft.

If upon finishing that you wished for less brevity, wished for more E.B. White, simply read it again. Won’t take long, and it’ll be time well spent. And just ignore the three or four places where White violates the maxims of Strunk & White.

It’s been a while since I flogged my own book. So ace marketer that I am, let me address the matter here. The Man Who Signed the City: Portraits of Remarkable People gathers profiles written over a 35-year span. Subjects range from a classical pianist to a deaf boxer, an acclaimed humorist to an English scholar who has toured with Björk. I also have an essay included in the anthology Good Roots: Writers Reflect on Growing Up in Ohio, where I’m in exceedingly good company—Anthony Doerr, Ian Frazier, Susan Orlean, Mary Oliver, P.J. O'Rourke, and more.

As always, thank you for reading.

Member discussion